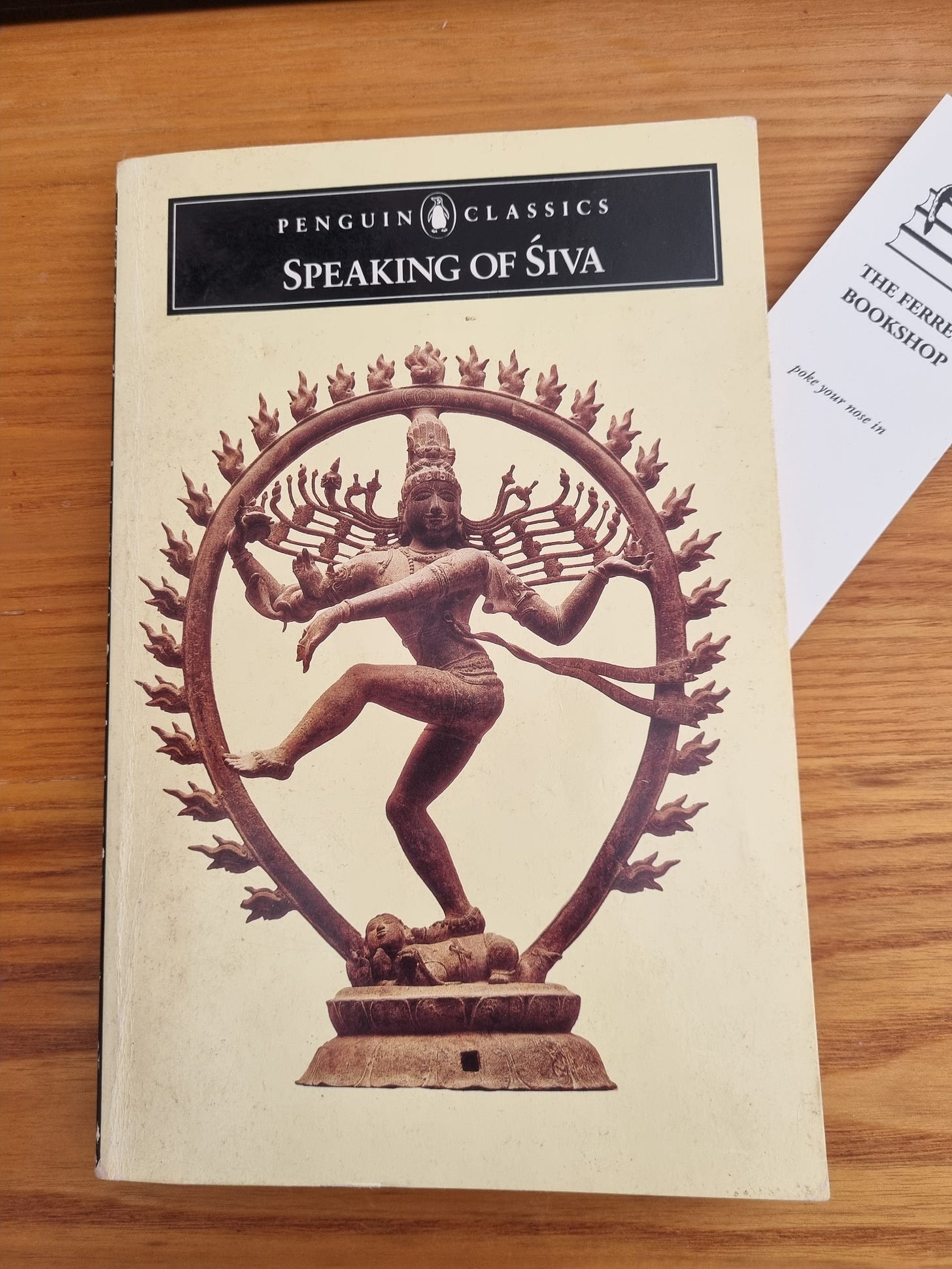

A few summers ago, I picked up a book on Medieval Indian poetry at a second-hand bookstore. This slim Penguin paperback was wedged between glossier tomes, the cover non-descript, and the yellowing pages almost falling apart. Little did I anticipate that I would uncover agonisingly living words from a thousand years ago, presenting compelling ideas for a 21st-century approach to rebellion.

In the mother’s womb the child does not know his mother’s face nor can she ever know his face. The man in the world’s illusion does not know the Lord or the Lord him. (Devara Dasimayya, 11 century CE)

The War Against Structure

Poetry rejects the premeditation required in most other forms of literature, and this intrinsic rebellion makes it an effective vehicle for protest. It’s no surprise then that the great Indian saints of the Bhakti movement manifested their rebellion through the non-conforming freedom of oral poetics.

For context, the bhakti protest movement emerged in the Indian subcontinent around the 6th century CE as a grassroots revolt against Hindu orthodoxy, especially its long-running support of the caste system.

Ancient Vedic literature often speaks in allegory, opening it to numerous (mis)interpretations. For example, many Indian temples are built in the image of the human body, per Vedic philosophy. The head is described as the Brahmin (priest), and the feet as the Sudra (pauper). This body metaphor conveys that the temple of God lies within every human being and that written knowledge (head) must be supported by experienced wisdom (feet). As time passed, this ancient, codified script was flipped, and the metaphoric temple was reinterpreted as a literal tool for control by hierarchy.

Counter-structuralism as a literary and political device.

The orthodoxy’s literary ideal was impersonal and esoteric, written in the priestly languages, mostly Sanskrit; hence, it was intended to be understood by few. The bhakti poets retaliated in the form of oral vacanas (free verse), explicitly choosing the local dialects of the working masses.

With your speeches and arguments

you build chains of words

but cannot define the spirit.

(Allama Prabhu, 12th century C.E)Much like the rhythmic speech of modern rap, the vacanas are intensely personal, playing with tone, instructions, warnings, pleas, curses, questions and answers, oaths and outcries. Bhakti poets directly express themselves and their personal relationship with the object of their devotion. Unlike orthodox hymns, which are often concerned with the object (the worshipped), bhakti vacanas focus on the subject (the worshipper), directly expressing the devotee’s inner state.

Sometimes, Sanskrit was included in these vacanas for effect and contrast, in the same way that Shakespeare utilised Greek and Latin. For example, the Sanskrit ‘sneha’, commonly understood as ‘friendship, fondness, love, attachment’, etymologically means ‘sticky substance’, and its use in vacanas invoked its multiplicity of meanings. In this way, the priestly Sanskrit language became a symbol of abstraction.

Where esotericism in orthodox literature was meant to conceal the secret doctrine from the uninitiated, in vacanas, the use of enigmas, paradoxes and riddles was intended to confuse bookish intelligence, hence challenging the priestly ‘head’ to ‘look through the glass darkly till it sees.’

For all their search they cannot see the image in the mirror. It blazes in the circles between the eyebrows. Who knows this has the Lord. (Allama Prabhu, 12th century C.E)

Devotion as rebellion

Rebellion does not always arise as a response to restriction. Though anti-structural in appearance, such movements are not always about destroying all structures. Rebellion emerges when a larger societal construct becomes parasitic and violates its own social contract.

The bhaktas rebelled against a pre-established world that had become a dangerous, highly limiting artefact of the past at the expense of the future. Through their poetry, the great bhakti saints urged their subjects to distinguish experience from The Experience, the latter being the ‘unmediated vision, the unconditioned act, the unpredictable experience’. They emphasised the original inspiration behind tradition over the ritualised practice of traditionalism and, therefore, a revival of true and present experience. In encouraging self-realisation, the bhaktas elevated radical, loving individualism as a distinctly social responsibility.

Though Bhakti's essence at the time was deemed antisocial in its desire to ‘unmake and undo the man-made and openly violate expected loyalties’, its principle of Loving Rebellion attracted many followers seeking to return to The Experience. By favouring the doctrine of the mystically chosen, the bhaktas formed small counter-structural communities (plagued with their challenges, of course), replacing the orthodoxy’s preferred social hierarchy-by-birth with a mystical hierarchy-by-experience.

As is often the case, the change brought by these great saints was eventually absorbed and diluted into the collective, feeding new forms of traditionalism. However, the vacanas maintained their original saintly code, carrying the required charge to survive through the ages.

That the thousand-year-old words of the Bhakti revolution have endured should offer inspiration to modern writers that we too must endure, no matter how futile our creative efforts seem today, so that a thousand years from now, whoever remains might find in our words the necessary human ingredients for their loving struggle.

Looking for your light, I went out: it was like the sudden dawn of a million million suns, a ganglion of lightnings for my wonder. O Lord of Caves, if you are light, there can be no metaphor (Allama Prabhu)

The Briefest summary of the Bhakti Movement that happened in India, mostly in the peninsular part in central and southern regions. A modern compendium on Saivism is elaborated in the book ‘Siva Saayugnyam -Merging With Siva’.